Obesity is a medical condition in which excess body fat accumulates to the extent that a patient’s health may be adversely affected. Although the prevalence of morbid obesity has remained stable over the past decade, it is still quite high with significant effects on individuals and healthcare costs.1 The health consequences of obesity range from serious chronic conditions that reduce the general quality of life to significantly increased risk for premature death.2,3 Morbid obesity is associated with a greater incidence of medical and surgical pathologies. The obesity epidemic is taking a toll on the US economy by adding an additional estimated US$147 billion in healthcare costs.4

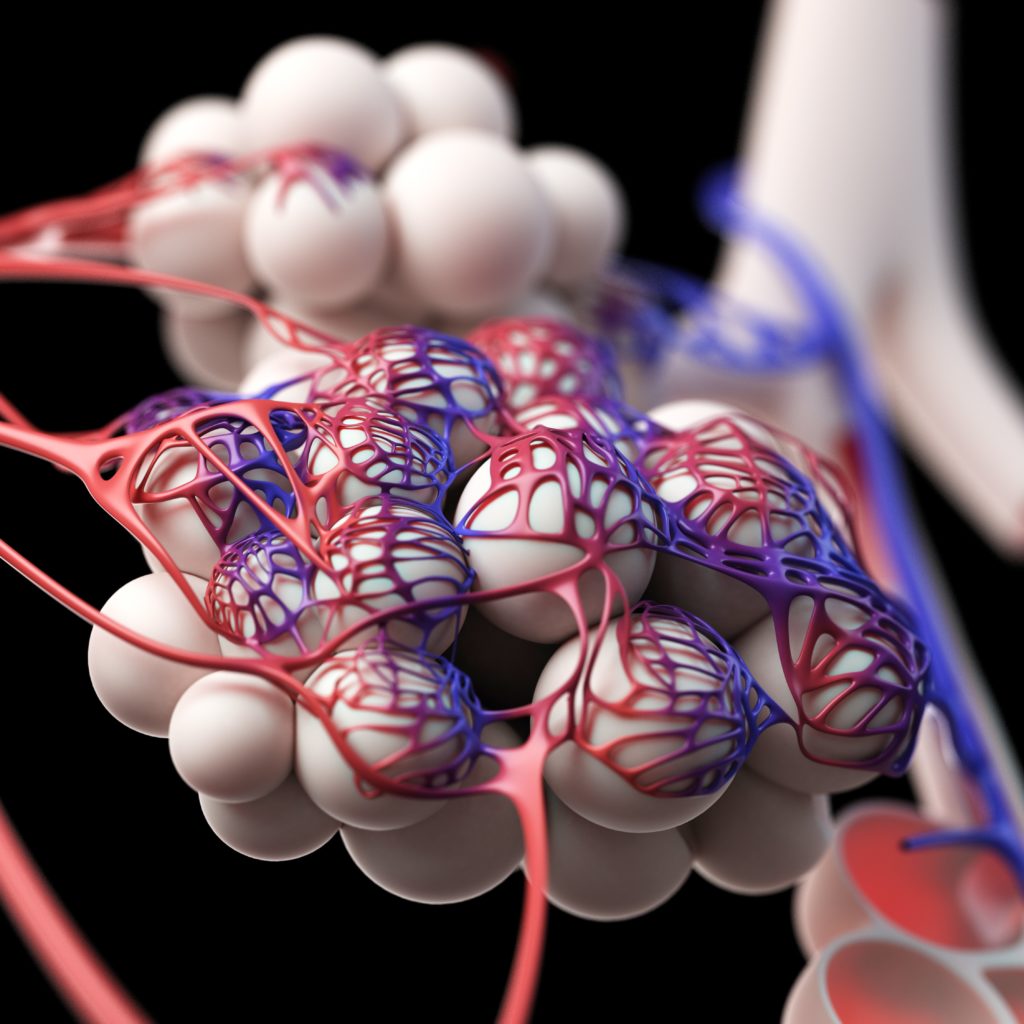

Obesity directly impairs the respiratory system in a number of ways. Carbon dioxide production is a function of body weight and, therefore, is increased in obese individuals. Ventilation/perfusion mismatch is more pronounced in obese patients due to small-airway collapse from decreased chest wall compliance. The lung bases have sufficient perfusion but are hypoventilated due to airway closure and alveolar collapse from the added weight of the chest wall. The result is a decreased functional residual capacity that can lead to hypoventilation (obesity hypoventilation syndrome) and hypoxemia, especially in the supine position. Respiratory muscle strength in the obese is likely to be compromised as the load of the extra adipose tissue is too much to handle. These patients are severely limited in terms of exercise capacity as well as ventilator reserve, which is key when these patients require mechanical ventilation.

The care of obese patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) poses special challenges in terms of both clinical care and safety. Specifically designed beds are required to accommodate the size and weight, and significant challenges exist in mobilizing or transporting such patients. Obese patients in the ICU are at higher risk for pulmonary emboli, cardiovascular compromise, esophageal reflux, and aspiration. Obesity also affects the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of many drugs due to changes in tissue distribution, hemodynamics, and blood flow to adipose, splanchnic, and other tissues. Plasma composition and liver and kidney function are also altered.

Airway management is complicated in obese individuals by excessive tissue hindering bag-mask ventilation and direct laryngoscopic view as well as interfering with the actual placement of the tube. A large neck with limited mobility, decreased mouth opening, large tongue, and short sternomental distance can pose serious challenges during endotracheal intubation attempts. Intubation is usually done in the supine position but, as mentioned above, putting obese patients supine can result in hypoventilation and rapid hypoxemia, so there may be less time to place the airway before hemodynamic collapse occurs. Equipment selection must be carefully considered prior to airway management procedures in obese patients. Other than routine laryngoscope blades and endotracheal tubes, equipment should include laryngeal mask airways, flexible bronchoscopes, and an emergency cricothyrotomy kit. If the obese patient requires a tracheostomy, special longer tubes may be required to traverse the excessive neck tissue to reach the trachea.

Ventilating the morbidly obese individual is extremely difficult. Many obese patients benefit from noninvasive ventilation (NIV). However, maintaining an adequate mask seal is complicated by excessive tissue.

Special masks (fullface masks) are often time required to facilitate adequate ventilation. Invasive ventilation is also much more difficult due to alterations in lung volumes and respiratory system mechanics. Current mechanical ventilator practice is the use of low tidal-volume ventilation with adequate positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and an airway plateau pressure (Pplat) limit of 30 cm H2O. However, this may not apply to morbidly obese patients. The Pplat is derived from transpulmonary pressure and the pressure to overcome chest wall compliance. Since the chest wall compliance is much lower in obese individuals, more pressure from the ventilator (in particular PEEP) may be needed to adequately ventilate and oxygenate. However, there is no accepted way to calculate what extra pressure that is needed and still safe for the patients. Using the esophageal balloon to calculate pleural pressure (pleural pressure has been used as a surrogate for pressure to overcome chest wall compliance) may give a good regional indication, but the pleural pressure almost certainly various in different areas of the lungs. As a result, morbid obesity is associated with prolonged mechanical ventilation and extended weaning periods. The extended periods of mechanical ventilation pose an additional threat in the form of ventilator-associated events.

Once the morbidly obese patient has recovered to the point of potential liberation from mechanical ventilation, some special considerations need to be taken into account. Doing a spontaneous breathing trial on a morbidly obese patient in the supine position has the potential for ventilatory compromise due to the excessive weight in the chest wall. These patients probably need to have the SBT performed in the sitting position. Not only will it prevent respiratory compromise but being in this position will more accurately portray whether or not the patient is ready for extubation. Many of these patients will require NIV once extubated, at least temporarily. In the potential event of needing to reintubate, appropriate equipment should be readily available as it may become an emergent difficult intubation scenario.

In summary, although the prevalence of obesity has stabilized, it is still quite high. Morbidly obese patients pose many additional respiratoryrelated challenges during their clinical course. Clinicians need to be aware of these challenges due to alterations in respiratory mechanics, lung volumes, and muscle strength to provide optimal respiratory care to this patient population.