Diagnosis Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias1 and accounts for about 20 % of all interstitial lung diseases (ILD).2 IPF should be considered in all adult patients with unexplained chronic exertional dyspnea,3 though it is rare in patients less than 50 years of age.4,5 The latest guidelines for diagnosis require exclusion of other known causes of ILD and presence of either a characteristic pattern on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) or specific combinations of HRCT and surgical lung biopsy with the pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP).3 Other disease processes that may cause UIP include collagen vascular disease (CT-ILD), drug toxicity, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (cHP), asbestosis, and Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome.6 Diagnosis of an underlying cause, if known, is of great significance in terms of treatment and survival. For instance, in one study, patients with UIP secondary to CT-ILD lived 63 % longer than those with idiopathic UIP.7

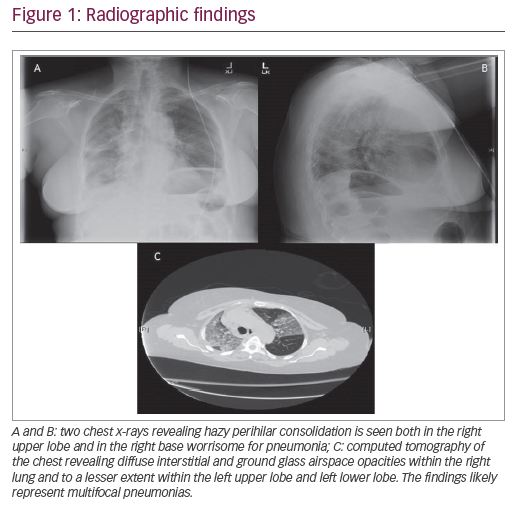

Classic HRCT patterns seen in IPF include a basilar and subpleural predominant distribution of reticulation and honeycombing, commonly with, though not requiring, traction bronchiectasis.8 Presence of ground glass does not exclude UIP so long as there is a greater degree of reticulation.8 Emphysematous changes may complicate HRCT interpretation and has been shown to result in mistaking UIP for chronic pulmonary emphysema with fibrosis (CPEF) as well as nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP).9 Appearance of the UIP distribution may be asymmetrical in up to 25 % of cases.10

The most common differential diagnoses for IPF are cHP, CT-ILD, and pneumoconiosis with particular emphasis on asbestosis.3 Concomitant features such as centrilobular nodules, air trapping, and relative sparing of the bases may be suggestive of hypersensitivity pneumonitis; pleural plaques suggest asbestosis; and septal or bronchovascular nodules may be present in sarcoidosis.11 CT-ILD should be considered in the presence of pleural effusion and/or pleural thickening, as well as esophageal dilation.11

Differentiating cHP from UIP/IPF may be difficult, as many times the offending antigen may not be discoverable.12 While bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) showing >40 % lymphocytes suggests a diagnosis of cHP and gene expression signatures have been shown to distinguish UIP from cHP,13 retrospective data suggest only 8 % of patients with a UIP pattern on HRCT have BALs suggestive of alternative diagnoses,14 and hence current guidelines recommend against routine BAL when evaluating for IPF.3IPF may present with a low-titer positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) and/or rheumatoid factor (RF) at a rate similar to that of healthy controls.15 In such patients, further evaluation for connective tissue disease (CTD) should be pursued, including both clinical and serologic workup. In the absence of additional evidence for CTD, a diagnosis of IPF may be appropriate, though periodic repeat evaluations for CTD should be done.3 Distinguishing idiopathic pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) from CT-ILD is critical, but difficult, due in part to the lack of reliable biomarkers.16

Failed Therapies

Potentially harmful medications in the treatment of IPF include warfarin17 and the combination of prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine.18 Sildenafil has failed to show improvement in forced vital capacity (FVC), dyspnea score, and mortality.19,20 A signal of harm was displayed with the use of selective endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA), ambrisentan, even in the presence of pulmonary hypertension (PH).21 In general, nonselective ERAs (bosentan, macitentan) should not be used in IPF, though it remains unclear if there may be a beneficial role in patients with PH secondary to IPF.22–24

Current Principles of Management Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is seen in up to 90 % of patients with IPF, but often clinically silent.25–27 Antiacid treatments may decrease the risk of microaspiration-associated lung injury and have been shown to decrease the rate of FVC decline.28,29 Most studies have included proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) more than histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), without a recommendation for one class over the other. More recently, PPIs have been suggested to have more pleiotropic effects, including suppression of profibrotic proteins.30,31

Pirfenidone

Pirfenidone is an antifibrotic agent first approved for use in IPF in Japan in 2008 following a trial that showed a 43 % reduction in the rate of decline in FVC and improved progression-free survival.32 This was followed by two CAPACITY (Clinical Studies Assessing Pirfenidone in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Research of Efficacy and Safety Outcomes) trials.33 The first trial, 004, showed a decline in FVC of 8.0 % after 72 weeks with 2,403 mg/day versus a 12.4 % loss in the placebo group. The 006 trial, however, did not maintain this effect through 72 weeks. Pooled data from both trials suggested benefit, though the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requested another study be done to clarify the discrepancy. The ASCEND (Assessment of Pirfenidone to Confirm Efficacy and Safety in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis) inclusion criteria were stricter, requiring lung biopsy if HRCT findings were not classic for IPF.34 The 52-week protocol showed half the number of patients in the pirfenidone arm experienced a decline in FVC≥10 % compared with those in the placebo group. More impressively, 63 patients receiving pirfenidone experienced no loss of vital capacity, while this occurred in only 27 patients given placebo. Fewer patients in the treatment arm experienced a decline of ≥50 m in their 6-minute walk test. These results led to the FDA approval of pirfenidone for the treatment of IPF in the US in 2014. This year, a sensitivity analysis of ASCEND demonstrated that at week 52, the proportion of patients with a 10 % decline in FVC or death was decreased by 47.8 %, and the proportion of patients with no decline was increased by 132.5 %.35 The most common adverse effects of pirfenidone included cough, nausea, headache, diarrhea, upper respiratory infection, fatigue, and rash, leading to discontinuation of the drug in 14.4 % of patients in ASCEND compared to a 10.8 % placebo discontinuation rate. Elevation of liver enzymes >3 times upper limit of normal occurred in <3 % of patients.34 Later, 178 patients who had previously been randomized to the control group in CAPACITY were included in an open-label extension, RECAP. In this study, the mean decline in FVC at week 60 was −5.9 %, an even better outcome than in the CAPACITY treatment group (−7.0 %).36 New data recently presented at the CHEST 2015 meeting from a pooling of the CAPACITY and ASCEND trials indicate that pirfenidone reduced both IPF-related and treatment emergent IPF-related mortality (HR 0.55 and 0.47, respectively).37

Nintedanib Nintedanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor with multiple potential therapeutic pathways in the treatment of IPF, including inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFR), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), and basic fibroblast growth factor receptor (bFGFR), each having roles in either endothelial or smooth muscle cell proliferation, and/or fibrogenesis.38–40 In To Improve Pulmonary Fibrosis with BIBF 1120 (TOMORROW), nintedanib reduced annual FVC decline by 68.4 % (130 ml/year) (p=0.06 closed testing for multiplicity correction; p=0.01 hierarchical testing), led to less acute exacerbations (2.4 versus 15.7 per 100 patient-years; p=0.02), and led to a 4.8-point improvement in the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) (p=0.007).41 Later came INPULSIS-1 and INPULSIS-2 (Safety and Efficacy of BIBF 1120 at High Dose in IPF Patients I and II, respectively).42 Both were 52-week protocols where neither found a mortality benefit nor reduction in acute IPF exacerbation rate. However, patients on nintedanib had an average 52 % reduction in FVC loss, representing about 125 ml spared annually.42 The most common adverse event was diarrhea (>60 %), followed by nausea. Elevation of liver function tests occurred in about 5 % of patients on nintedanib. During the INPULSIS series, 10 patients on nintedanib suffered myocardial infarctions, compared with two patients receiving placebo. Worth noting is that some patients enrolled in INPULSIS were included with HRCT interpreted as “probable UIP” and not confirmed with biopsy. It is unclear whether this may suggest the benefit of nintedanib in non-UIP ILD or rather an underestimation of its effect in true UIP due to inappropriate inclusion criteria.

Comparison of the available data shows similar reductions in FVC decline of 45.1 % with pirfenidone, and 52.2 % with nintedanib. With time, nintedanib may show an improvement in mortality comparable to that of pirfenidone. The practical interpretation and application of the differences in data between the two drugs is unclear in that the groups of patients studied were not the same. The selection of one medication over the other should be done on a case by case basis, following a discussion with the patient regarding dose scheduling (nintedanib is twice daily, pirfenidone three times daily), adverse effects, and cost/ accessibility. Although there are plans to study the two drugs together, no data are currently available to support combination therapy or to prefer one drug over the other.

Current guidelines do not address appropriate timing for referral for patients with IPF for lung transplantation.43 Consider referring patients with IPF for lung transplant evaluation if they have dyspnea with routine daily activities and are requiring oxygen therapy with an anticipated survival of <5 years. Regarding single- versus double-lung transplant, a recent meta-analysis of available observational studies from 1990 to 2013 did not show any difference in mortality after adjustment for patient characteristics.44 Ongoing cell-based therapy trials may promote new directions in the management of this fatal disease.45

Conclusion

Despite the recent addition of two medications for IPF that slow lung function decline, IPF remains a deadly disease. Avoidance of smoking should be strongly advised, and poignant management of comorbidities such as GER should be undertaken. We have entered a new era in the management of IPF, but curing the disease remains a current goal.